Microservices interaction at scale using Apache Kafka

Intro

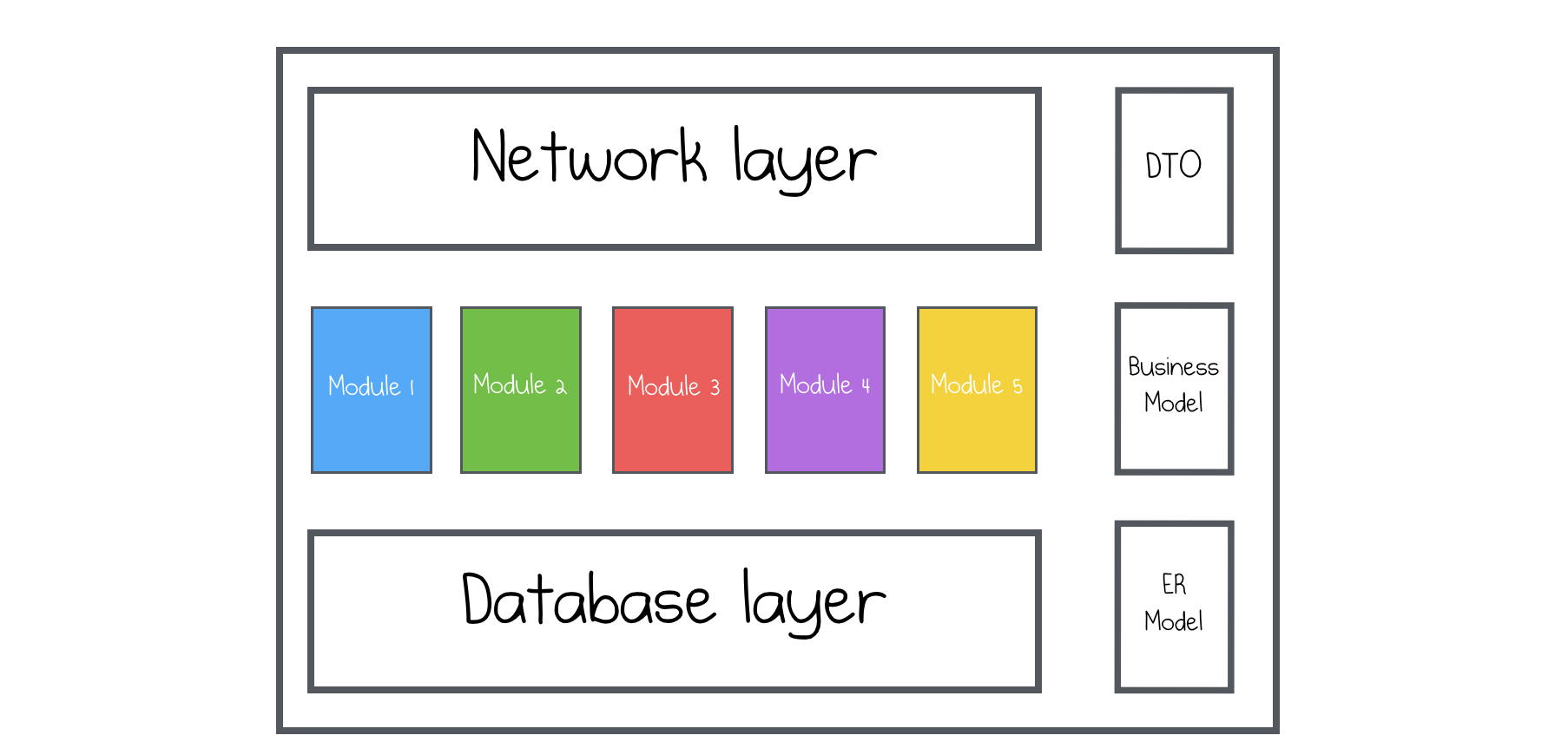

Why do people do microservices architecture? Let’s start with a review of a classical, old-school, n-tier application, which is often called a monolith:

Everyone worked with this types of applications, we were studying them in university, we did lot’s of projects with this architecture and at first glance, it’s a good architecture. We can immediately start doing systems on this architecture, they are perfectly simple and easy to implement.

But as such system becomes bigger, it starts receiving lots of different issues.

Everyone worked with this types of applications, we were studying them in university, we did lot’s of projects with this architecture and at first glance, it’s a good architecture. We can immediately start doing systems on this architecture, they are perfectly simple and easy to implement.

But as such system becomes bigger, it starts receiving lots of different issues.

The first issue is about scalability, it doesn’t scale well. If some part of such system will need to scale, then the overall system should be scaled. Since the system is divided into modules, it runs as one physical process and there’s no option to scale one module. This can lead to expensive large instances, which you will have to maintain.

The second issue is about engineers. Since it will become enormously big, you will have to hire a really big team for such system.

Evolution

How can you address this issues? One of the ways you can evolve is to make a transition to a microservices architecture

The way it works is that you have a bunch of services with separate independent deployment pipelines, separate teams, and separate codebase. This services can be better written, supported and scaled. In theory.

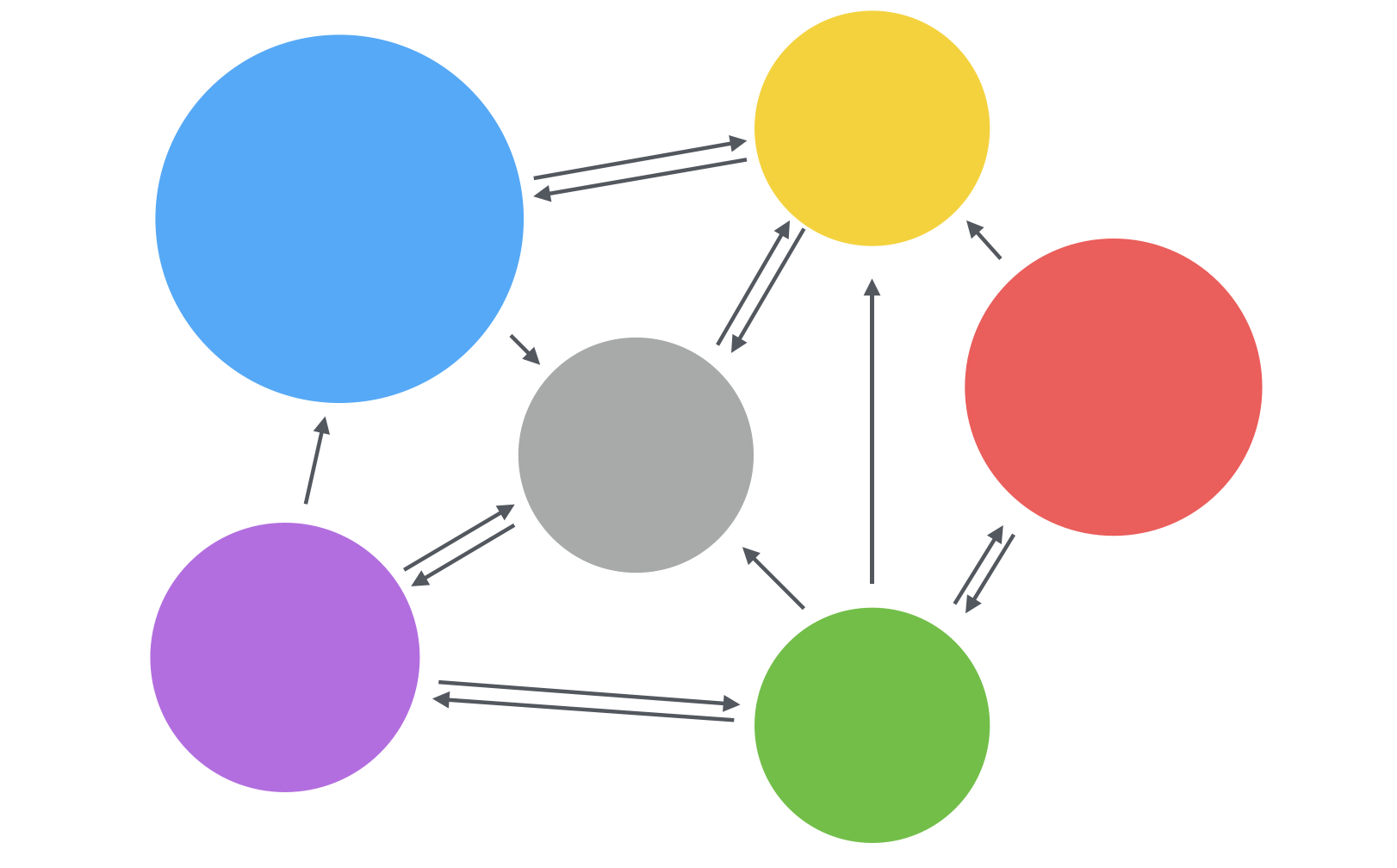

Here’s how it looks in practice:

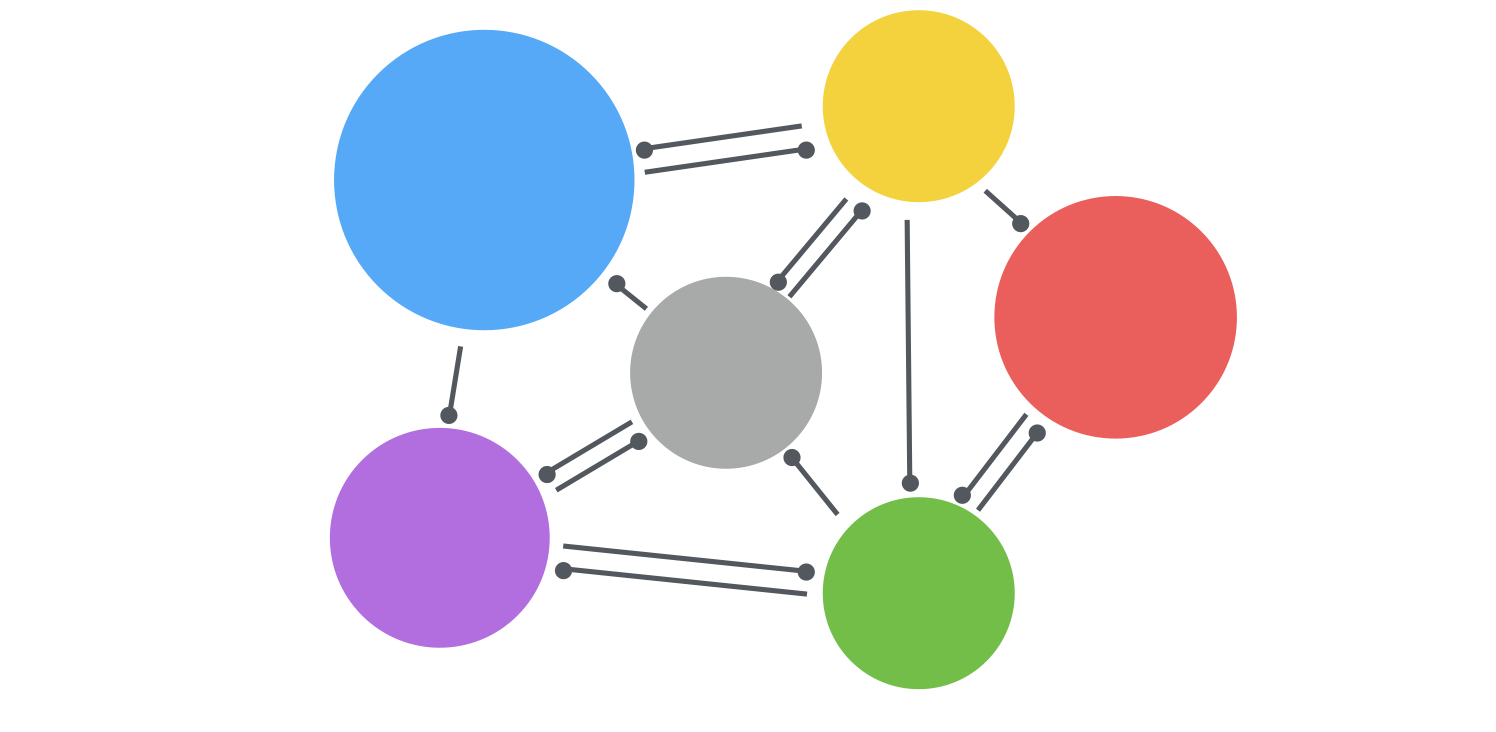

You will get a lot of different services, running across the network, having different approaches, some of them will occasionally fail, some of them will have lots of bugs. This is the world, where you will live.

Goals

What are the goals you want to achieve while migrating to microservices architecture? Of course, saying “I want to migrate to microservices, because I would like to split the monolith application” doesn’t answer any goals, by implementing it you can get even more problems, than you had before, so you have to think carefully about your goals.

Scaling in terms of people

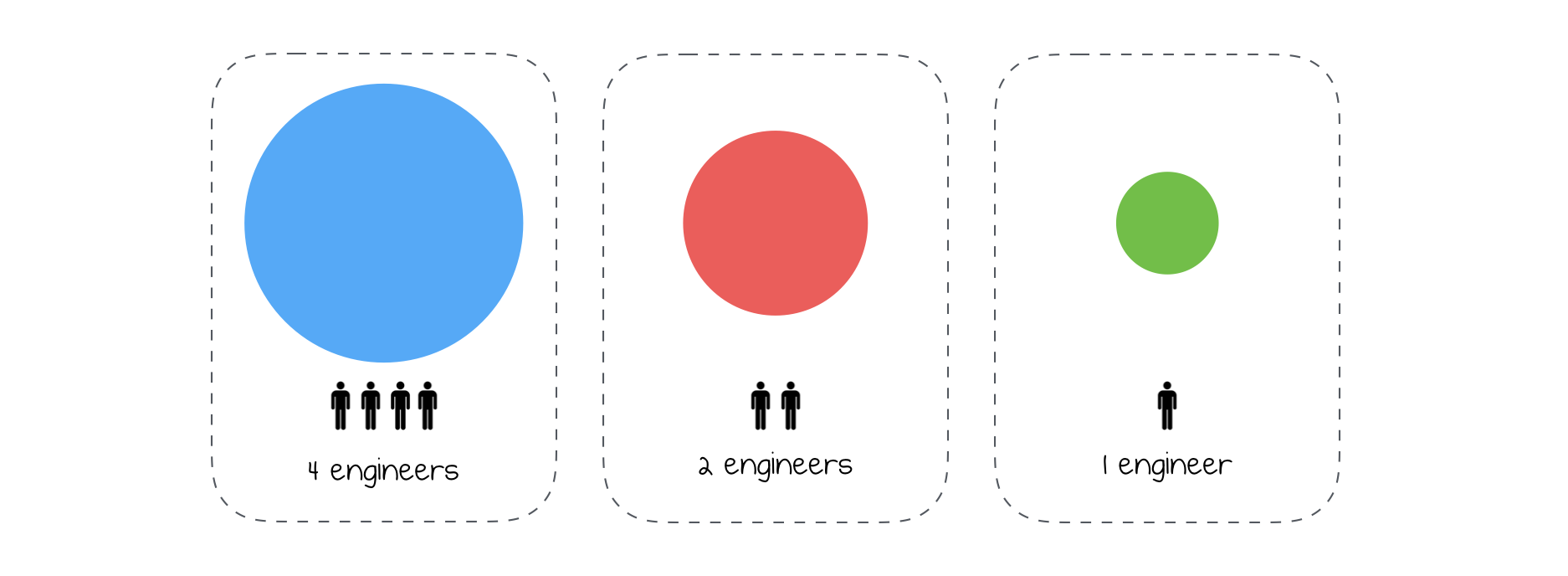

First of all, you would like to be able to scale in terms of people.

By working in monolith application, you had a lot of engineers inefficiently working on one big application. Now, you can manage them more effectively, because you can assign more engineers on some big services, fewer engineers on smaller services. You can follow so-called pizza team pattern or number of lines pattern. Personally, I think that the size of the team should depend on a scope of the context this service is responsible.

Scaling in terms of data

The second goal is about data. If you are migrating to microservices, then you should have enough data. This age is about different storages, so when migrating, you will get an option to choose the data storage you want. If you have some graph structures in your business domain, you can decide to use some graph storages like Neo4J. If you have search logic, then search indexes are for you. In case you have a non-stable schema, you can always decide to use NoSQL types of storages like MongoDB.

Service independence

And of course, you would like to be independent. Who doesn’t like to be independent?

The key idea here is that your service should be as much independent as he can. For sure, there will be lot’s of other services, and it would be a bad idea to communicate with all of them. So, this service will have a separate codebase, separate deployment pipeline. You will have separate meetings, separate projects in your issue tracking system, separate Slack channel, whatever.

Service communication

But companies are inevitably a collection of applications/modules/subsystems, which should work together to achieve one global result. In other words, your microservices should communicate. While working inside monolith, you couldn’t take it seriously, because you had only one single process with a bunch of modules. Now, as your application evolves, you have to share information between services, since you will have them running across the network.

So, what are the communication patterns for microservices? I will review three key patterns:

- Shared database

- Request/Response aka Shared interfaces

- Asynchronous messaging through a message broker

Let’s review all them, step by step.

Shared database

It’s the first and the worst communication pattern, which I know. The idea is that you have many microservices with a single database for all of them.

If you have many services, distributed across a network, you will probably want to have them independent. You can’t have them independent if they all are writing and reading from a single database? Even if this database is NoSQL, supports AP from CAP theorem(Availability and Partition Tolerance), you still need to have a lot of coordination around your database.

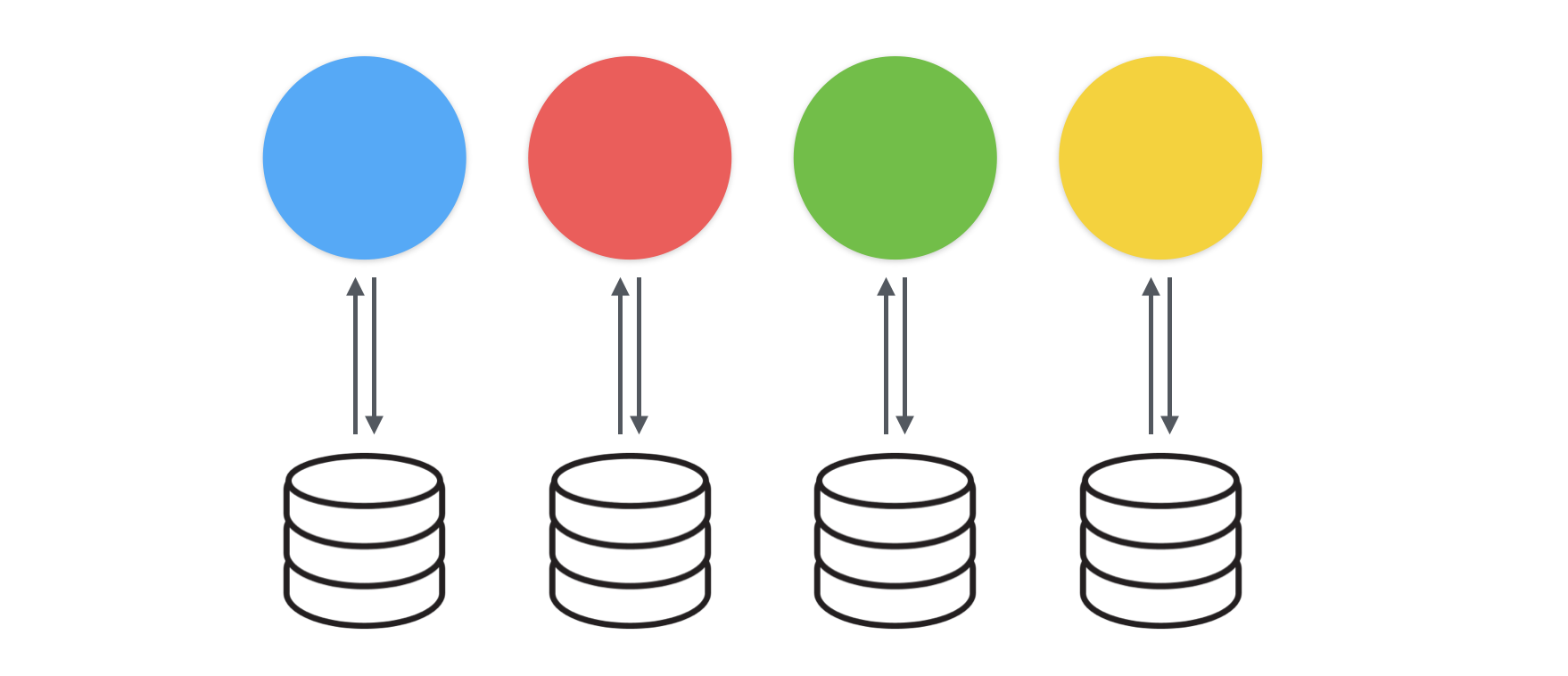

The true way to deal with databases in microservices infrastructure is to have them separate for every particular service. In other words, you have your database, you support it, you scale it according to your service needs.

Service interfaces

We live in a world of http endpoints and we naively think that communication between microservices can be organized using this abstractions. This pattern deserves to be partially implemented in modern microservices architecture, but it should be carefully reviewed first.

If you use service interfaces to query other services for some information, which you don’t store in your storage, then it’s perfectly okay. There are several reasons why you don’t have this information in your storage, for example, you are a small service with a small storage and the information that you are requesting is far too big to store in your little storage. However, if you want to use service interfaces for doing write operations, then you can get into lots of issues. I will explain them, step-by-step.

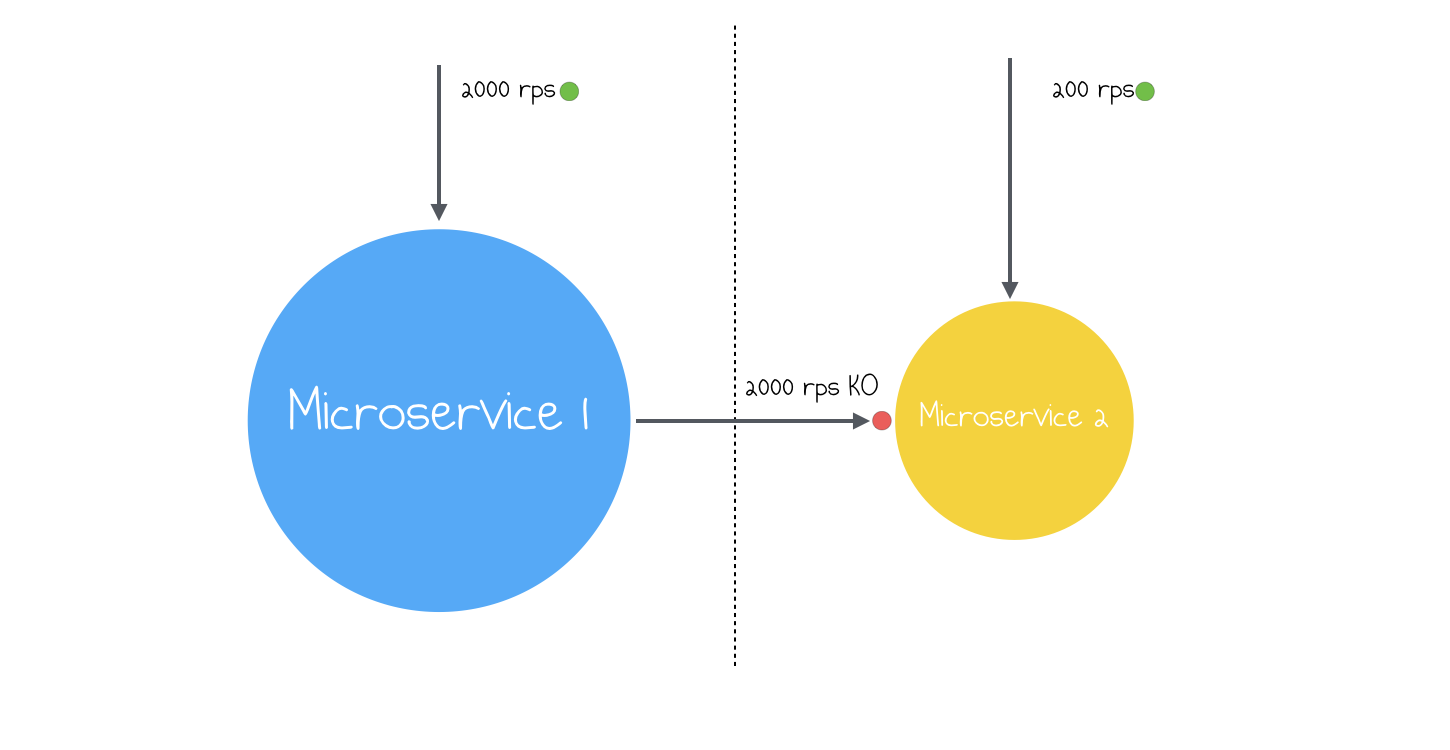

Service size

First of all, the size of different services is often different. So, if you decide to query some other service, think twice if you won’t overload it. If you ever worked with DynamoDB, you know, that it has a notion of capacity provisioning - you chose an optimal number of readі and writes. So, once I saw, how one service started to send requests to another service, which was using DynamoDB for storing its internal data. The number of requests per second was quite big and service started to fail.

First of all, the size of different services is often different. So, if you decide to query some other service, think twice if you won’t overload it. If you ever worked with DynamoDB, you know, that it has a notion of capacity provisioning - you chose an optimal number of readі and writes. So, once I saw, how one service started to send requests to another service, which was using DynamoDB for storing its internal data. The number of requests per second was quite big and service started to fail.

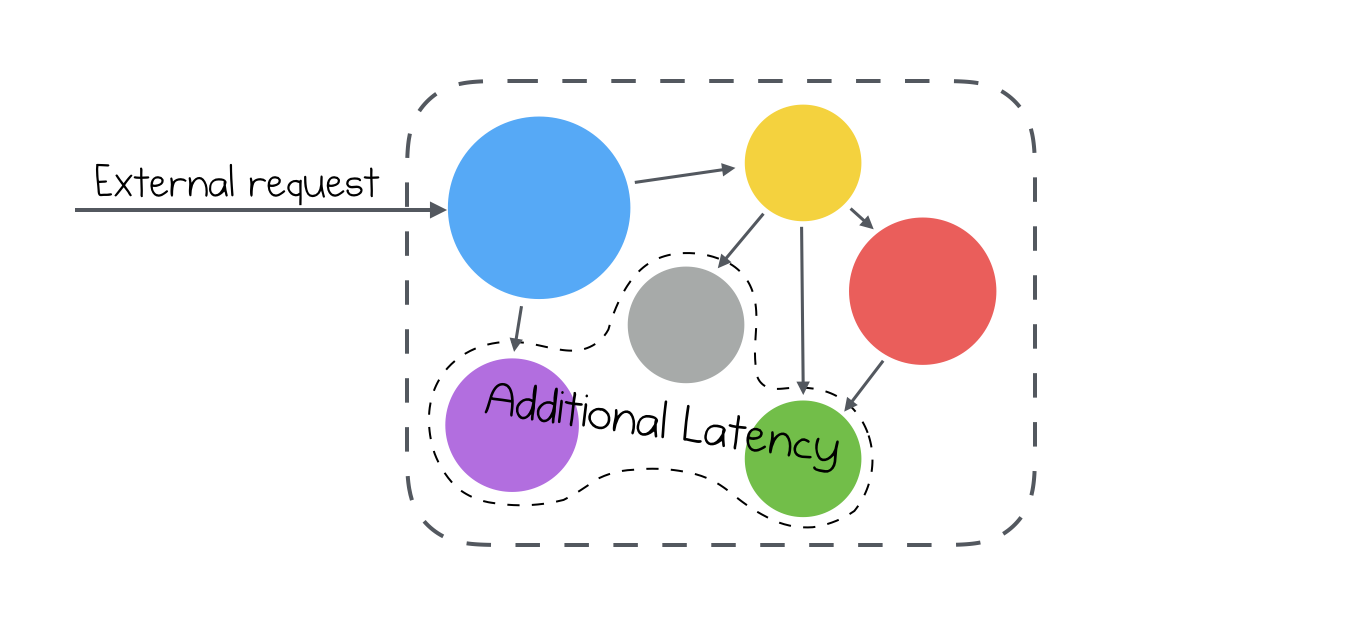

Critical path

When we are talking about microservices, we can assume that not every service needs to be a part of this critical path. Some of the services can do the job later. For example, if you are deleting some user from the system, you don’t need to update all the information in all services. You can do it later, without any problems.

Additionally, it brings bigger latency, your users will be affected and for sure, they won’t be happy with it.

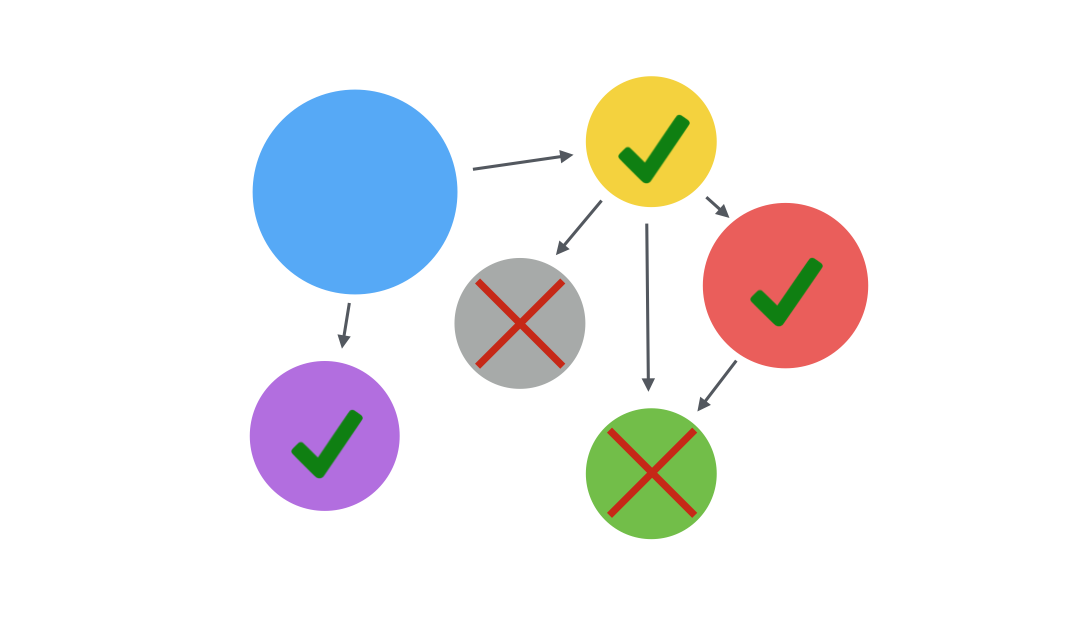

Consistency

And even if you had to update all the services immediately, I bet, you could do that without bringing inconsistency to your system.

Think about a case, when you are calling services one-by-one and one of the services fails. Some services are already executed, and in the middle of the process, one service fails. What would you do then? Well, you could introduce two-phase commit approach, but the problem is that not every database supports two-phase commits, and even if it does - revise CAP theorem, you can choose only two of three properties - Consistency, Availability, and Partition tolerance. Hopefully, you have Partition tolerance out of the box, and you can choose either Consistency or Availability. And it’s better to have an available system, rather than consistent. Furthermore, most distributed system nowadays can guarantee eventual consistency.

Asynchronous messaging

Service interfaces are sometimes a good approach for getting some real-time data, but the bad thing about them is that they introduce real-time coupling. Who worked some time in software engineering, knows, that the best option to avoid real-time coupling is to bring asynchronous approach. What does it mean in the scope of our microservices architecture?

It means, that we will have some level of abstraction, some entity, which will do the operation of transporting messages between different services. This level of abstraction is often called a message broker or a message queue. An entity, which receives some messages from one service, stores it somewhere and sends this message to all consumers, that are subscribed to receive such type of messages. Interesting, don’t you find? This way of transporting messages and doing synchronization brings more questions, than answers and needs to be carefully implemented. We will talk about this problems a bit later.

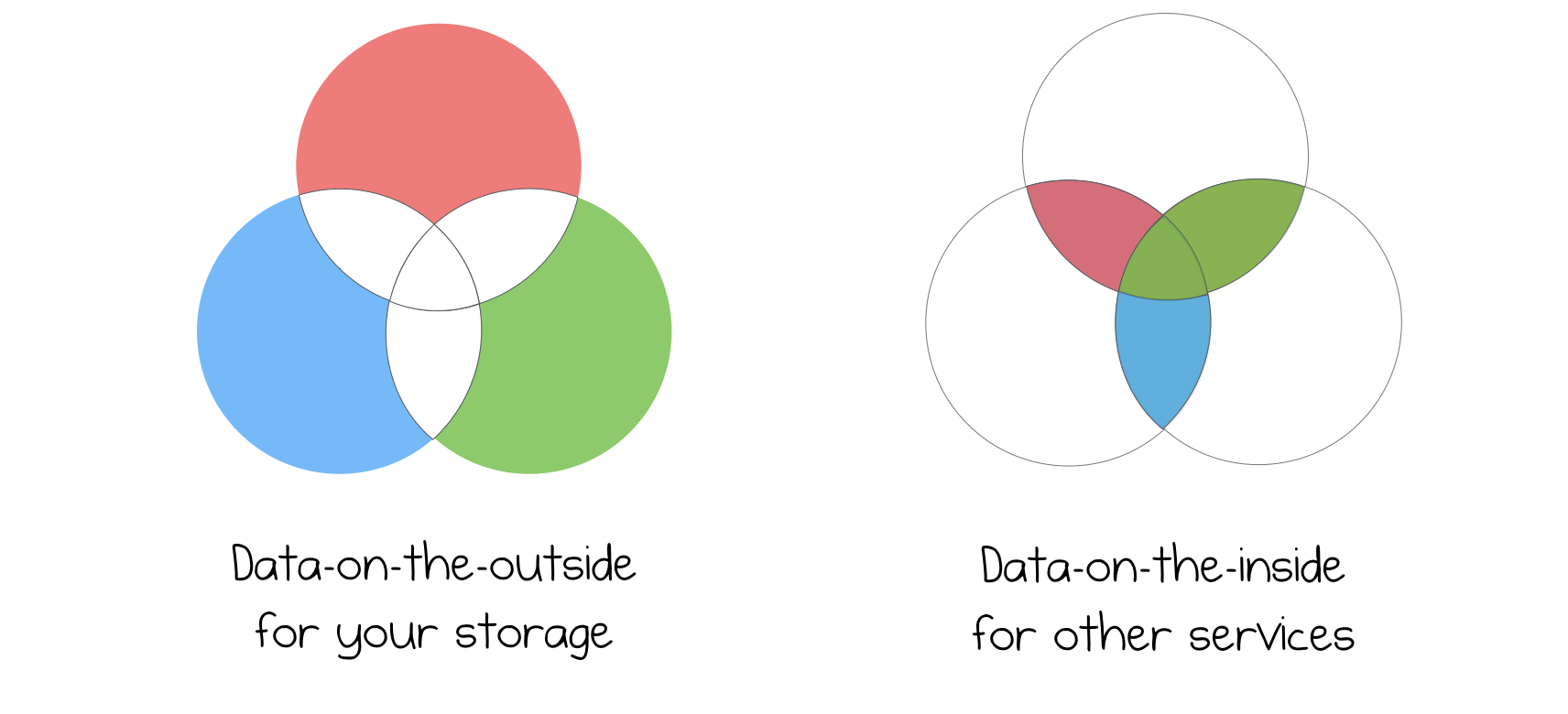

When we do such architecture, we can then clearly see, that there are two types of data, in our infrastructure - so called, data-on-the-outside and data-on-the-inside. First one is used as a source of truth, as a storage, for giving information to the outside world, for outside requests. Second is used as a data, shared inside infrastructure for all interested services.

This way of doing microservice communication is more natural, rather than doing communication each particular service.

More formally, the architecture is more pluggable, it’s a lot easier for the new service to start receiving existing data: you just start listening to specific information in message broker, and that’s it. Existing producers of such messages can don’t even know about this new service.

Apache Kafka

Apache Kafka is an example of such message broker. Created inside LinkedIn, it later became one of the best solutions in the market. It’s not a message queue, but rather a distributed, publish-subscribe messaging system. It is very fast, scalable and durable.

Here, in this article, we’d like to know how Kafka can improve our microservices, right? Let’s review a couple of patterns.

Event Sourcing

It’s the first pattern, which can be used together with Kafka. For those of you who don’t know what is Event Sourcing pattern, I recommend reading some articles. The idea is pretty simple - you use Kafka as an event-sourcing storage, for storing all the events. Then, you use Kafka Consumer for reading those changes. In microservices, it means, that you will design your requests according to the fact, that you will store a message in Kafka and process it later. This means you won’t be able to give an immediate answer and this forces you to change the way you process your data.

However, this gives you more options to work with your data. First of all, as you know, Kafka has an option to rewind messages for specific consumers. You just give an instruction, that you need to rewind it 2 hours behind and that’s it, your consumer will start processing older messages. That’s a good compensation for delayed processing, don’t you find? I didn’t mention debugging. As you store all the requests in Kafka, you will be able to analyze them in your non-production environment, find a bug in your code, fix it and rewind the messages.

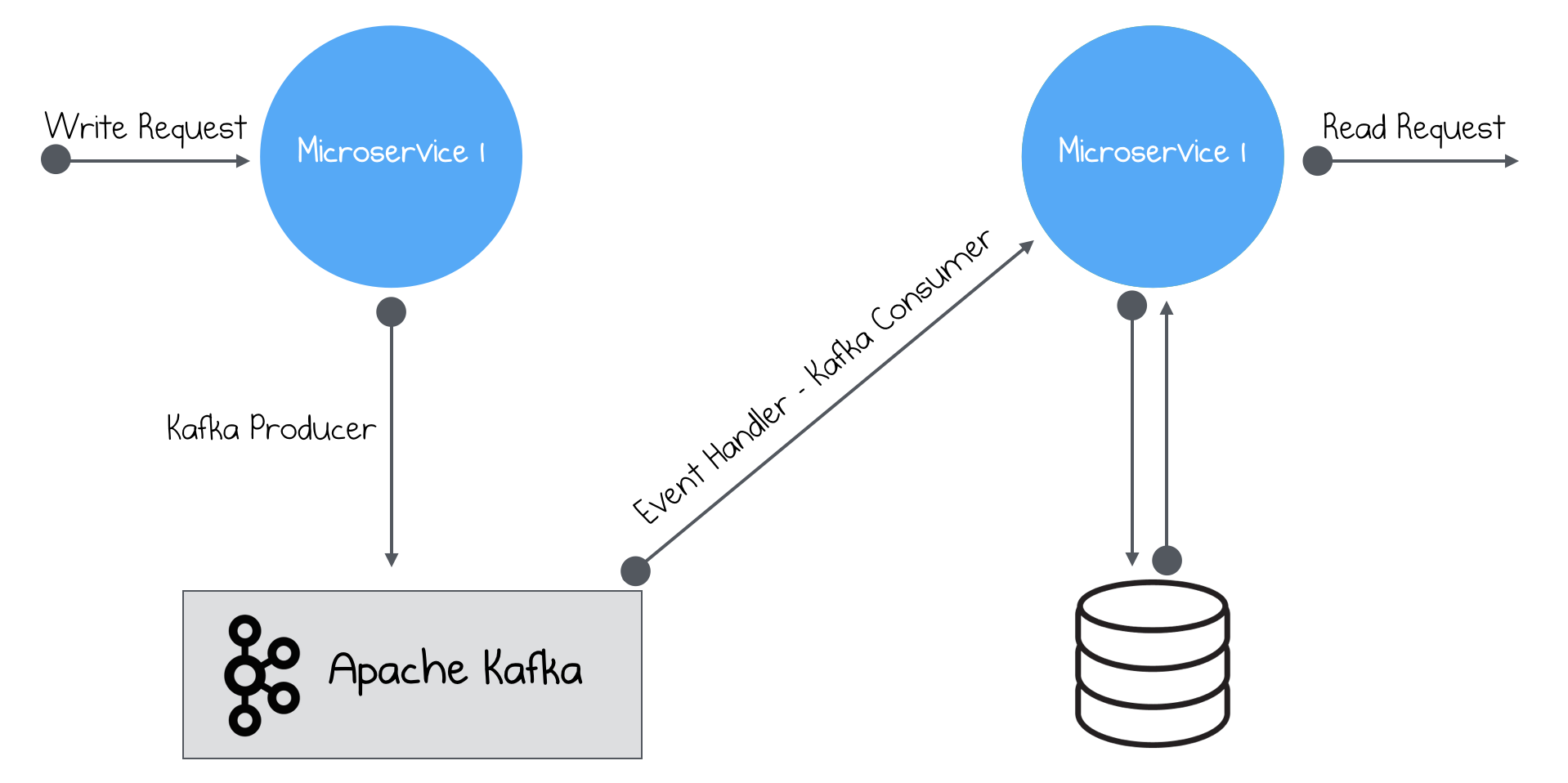

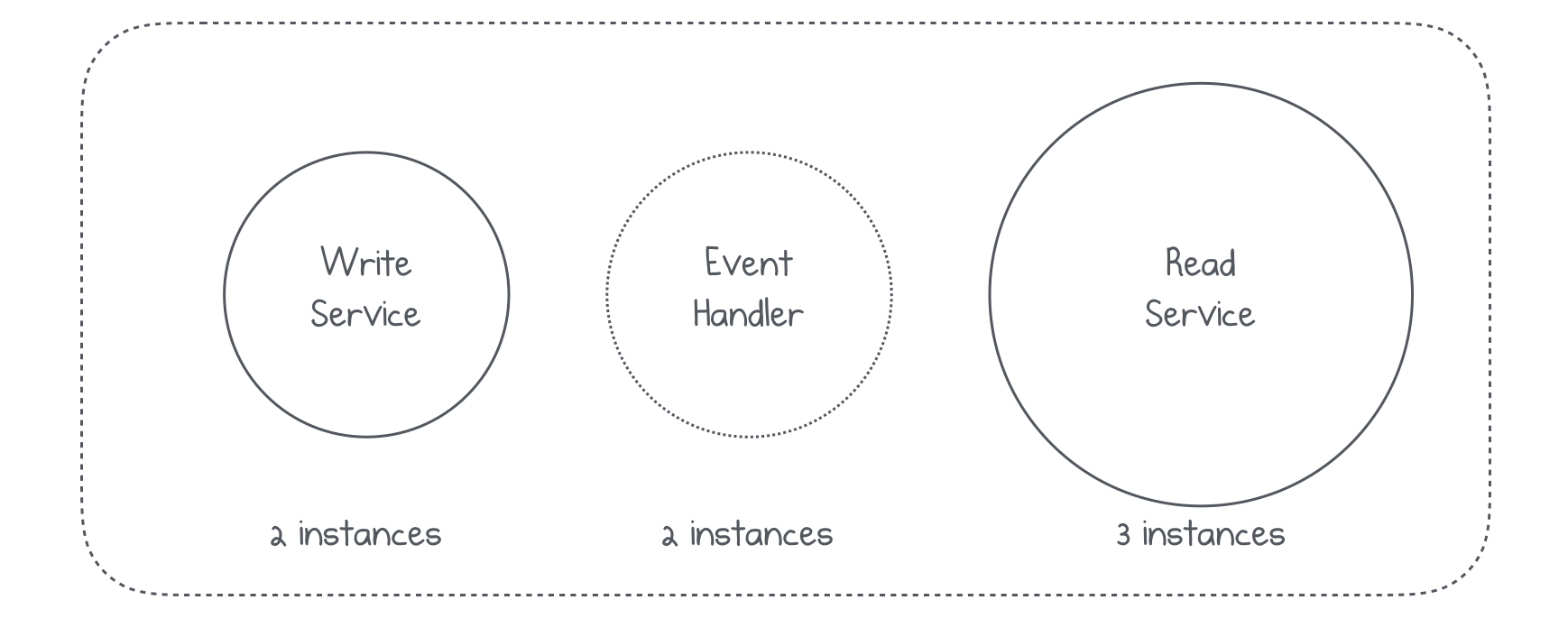

Another big advantage in having event sourced approach in your system is that you will have a better scaling opportunities. You will have three dedicated functions: writing to Kafka, reading from the Kafka(processing data to your separate storage) and reading from separate storage. Why don’t you create separate instances for all those three functions? Here’s how it should look:

By having this separation your will have the ability to create 1 instance of write service, 2 instances of listener and 3 instances of Read service. If for some reasons, you will need to scale and add more instances to the write services -there won’t be any problems.

I wrote a lot of text about event sourcing pattern, but I haven’t explained the relation with Kafka. Kafka fits well in event sourced systems, first of all, because of it’s design. It has a retention period for messages, which is exactly checkpoint pattern in event sourcing. It also has an option to save the latest version of your message, having the right to say that Kafka can be treated as a source of truth, in some situations. Kafka is also very fast, configurable and easy to use. That’s a perfect candidate for event sourcing approach.

Change Data Capture

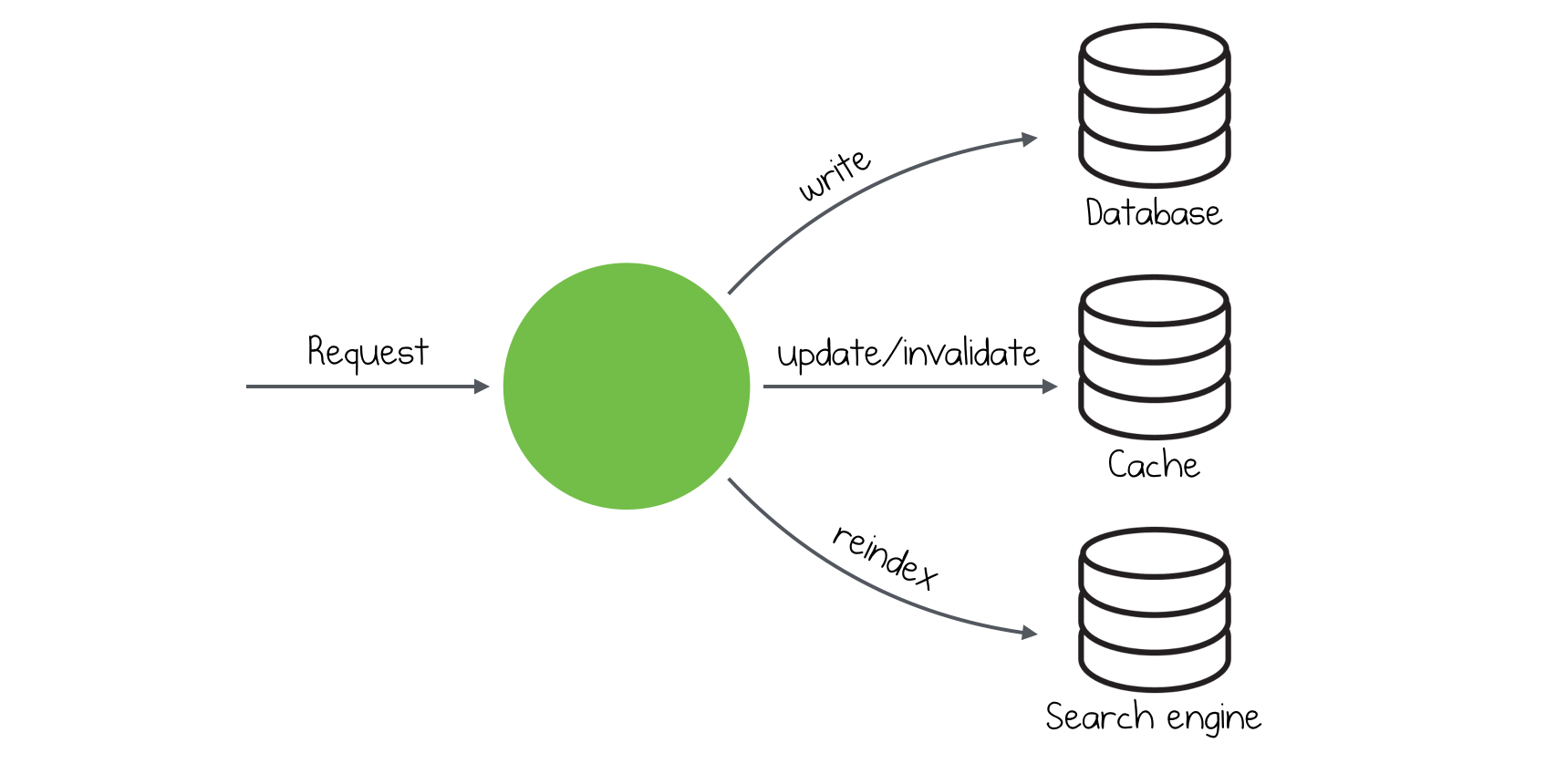

We’ve discussed event sourcing previously. While event sourcing intends to update it’s database after inserting to event store, CDC(Change Data Capture) approach works completely different.

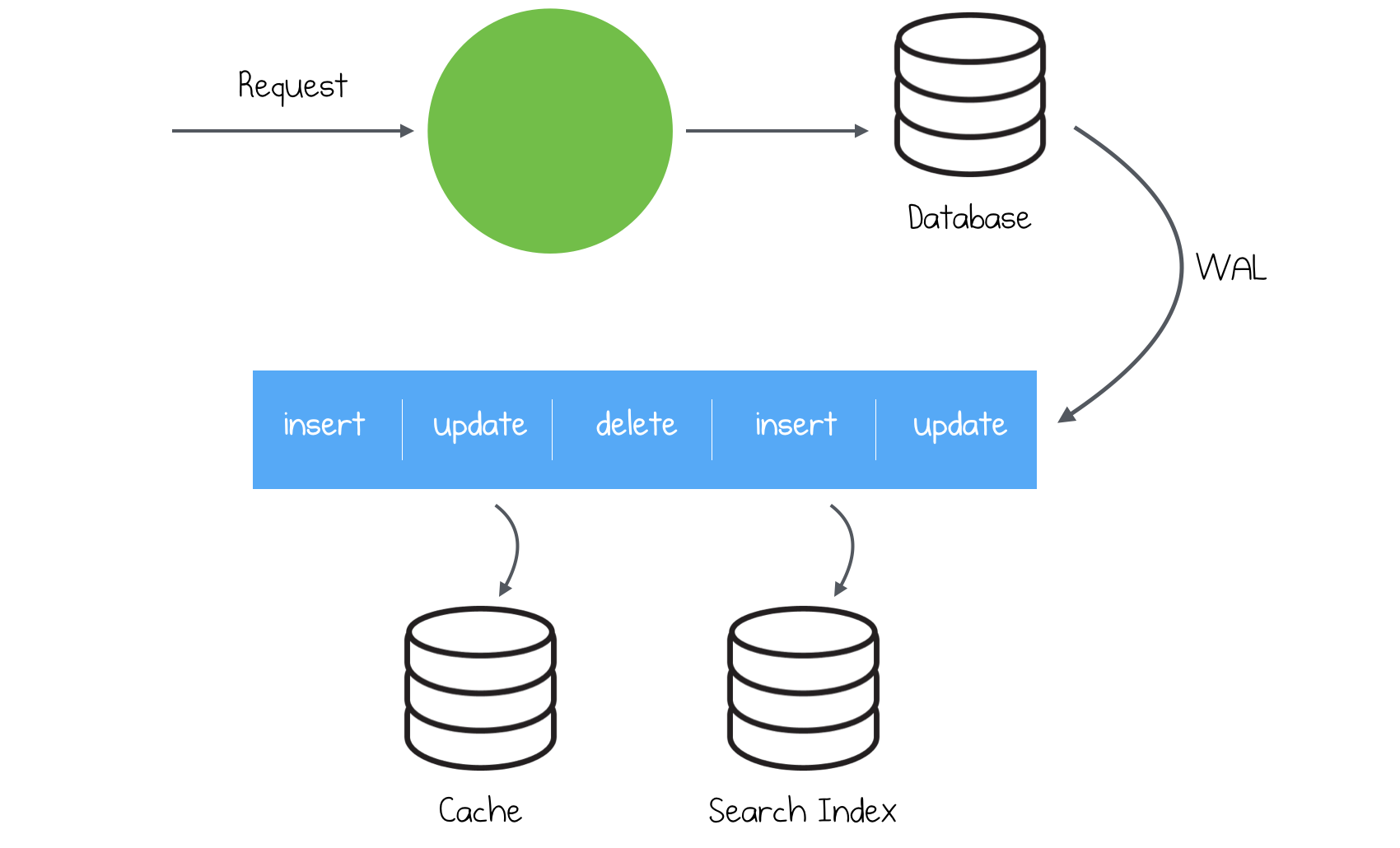

Before we discuss this approach, let’s imagine we have our microservice, it’s data storage and some message broker like Kafka. We would like to update our storage during each request and we also need to update Kafka, so other microservices can reach information about our updates. Does anyone see a problem here?

The problem is that we have two source, which needs to be updated. It’s almost impossible to save information in data storage and insert a new message in Kafka and have a consistent system. This approach suffers from race conditions and it’s very easy to insert a record in the database and have an exception in Kafka side. What should we do instead?

The alternative way is to continue inserts into our data storage and stop inserting new messages into Kafka. How is Kafka going to be up-to-date? Let’s think about what we’re inserting in Kafka. The truth is that we are inserting the same message(or almost the same), so the other consumers(microservices) can react on this event. Change Data Capture approach is getting fresh changes from the database and inserts them to Kafka.

For example, in PostgreSQL it uses a feature called logical decoding, introduced in 9.4 version, to read Write-Ahead Log of changes. You can find a lot of tools around, which provide CDC functionality. As I am using PostgreSQL, I know that there are such tools as Bottled Water, Debezium and a lot of smaller tools.

The process consists of two parts:

- Collecting all information from the table and putting it to the Kafka side

- Reading the new data and continuously inserting it to the Kafka.

The first part is quite big. It can take several hours before it finishes. The second step won’t stop and will continue putting data to the Kafka, so you can read it and react.

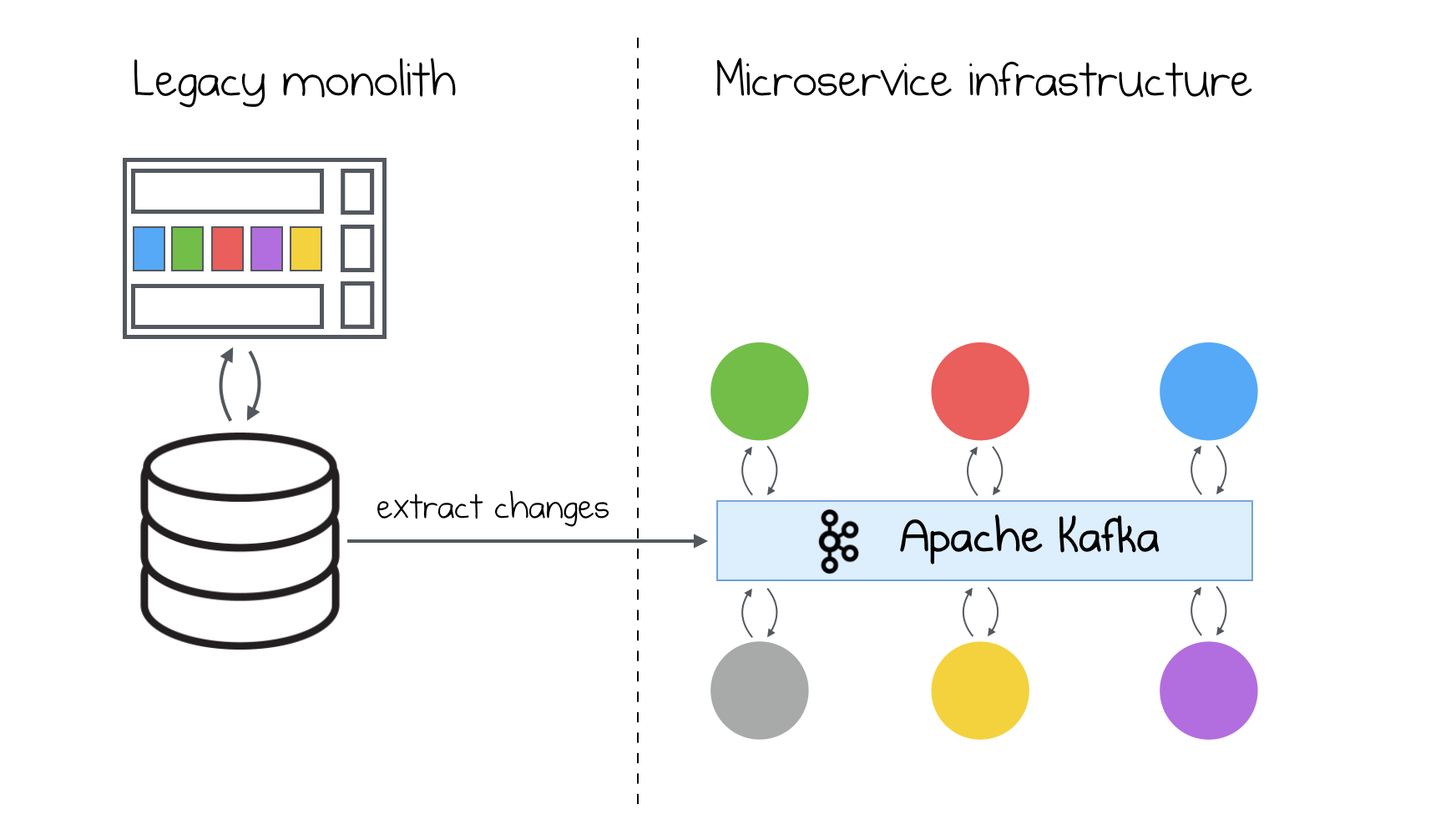

One of the biggest advantages, that I see is that we can adapt existing databases for streaming it’s data changes. For example you have a PostgreSQL database in some particular service and you have a request to stream your changes. Without a doubt, you can easily do that with one of the tools, provided above We can also adapt our legacy data storages to stream their changes. This can eliminate your ETL monsters, which are transforming data from your legacy side to your modern microservices.

Kafka Connect

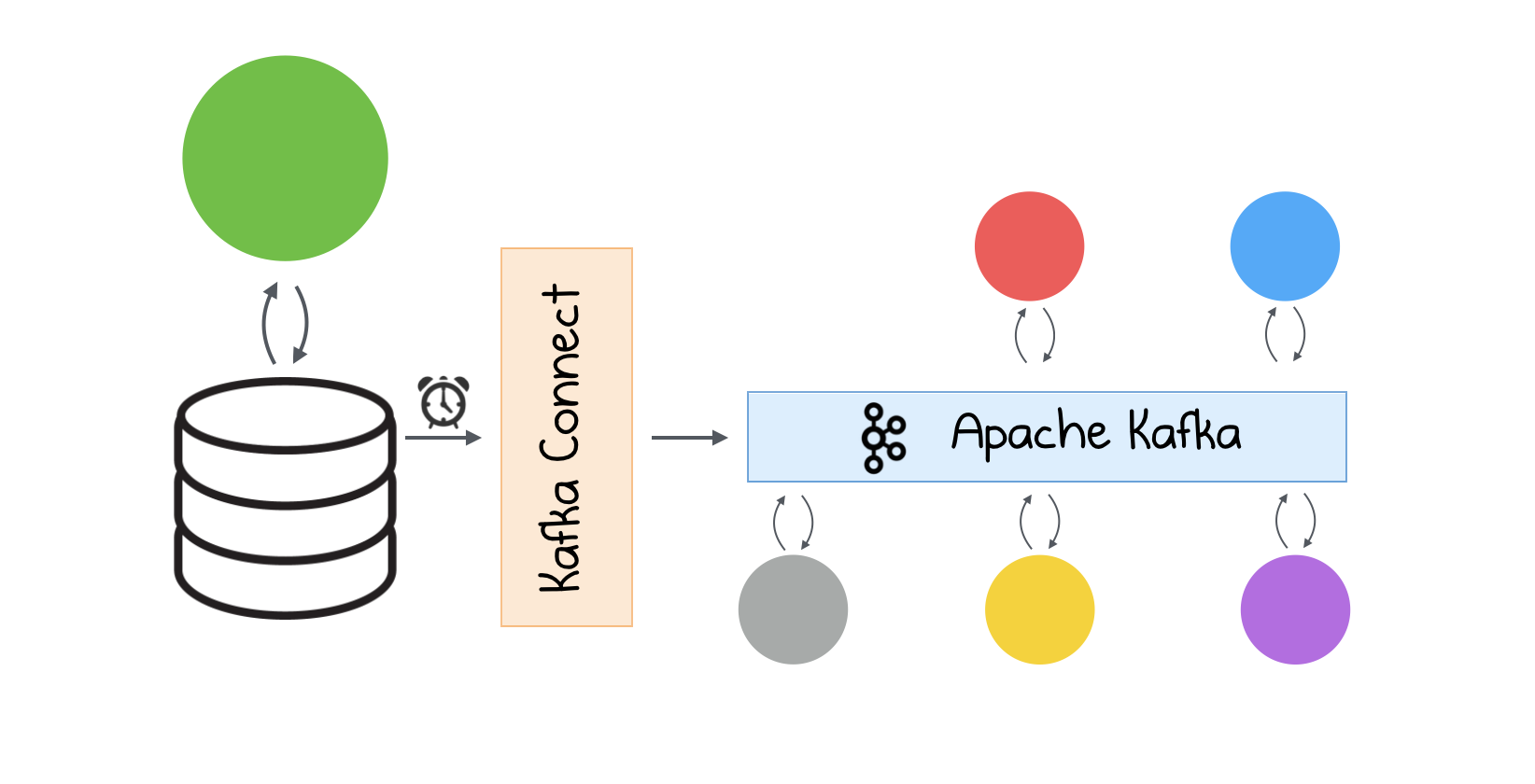

Finally, when you don’t want to use event sourcing pattern and you don’t have any CDC tools in your data storage, you can stick to Kafka Connect.

The idea is pretty much the same as in CDC, except that you will do a scheduled calls to the database to get a new data. This will, in fact, give additional load to the database. Furthermore, because you will do scheduled calls every period of time, your messages will appear in Kafka in batches, rather than in streams and if you choose a big interval of time to wait before each call, you will have your consumers waiting for the new data. For sure, Kafka Connect requires more configuration.

I encourage you to read more about Kafka Connect, there’s a very descriptive documentation, lot’s of articles and youtube talks about it.

Conclusion

I mentioned three patterns, which you can use inside your microservice architecture. This article is an introduction to the Kafka and microservices, I didn’t mention other patterns and if you know them - do a little comment and let’s discuss.

Here’s a video from Lohika Morning anniversary, where I spoke about Kafka: